According to Joyce Sexual Force Feeding Leads to

J oyce McKinney is one of those names that for people of a certain age opens a doorway into the past. To mention it is to be transported back to the 1970s, when there were only three TV channels, British food was awful, sex was naughty and Fleet Street was still the home of national newspapers. Back then computers were the preserve of boffins in white coats, but even if journalists had managed to lay their hands on some mainframe monster the size of a small house, and programmed it with all the ingredients of the perfect tabloid story, the results could never have matched the bizarre and compelling tale of a wannabe beauty queen's obsessional love.

Featuring a missionary, a kidnapping, bondage sex, naked photographs, a daring flight from justice, and even the Osmonds pop group, the story held the nation in its irresistible spell for the better part of a year. To some – not least herself – McKinney was the embodiment of the wronged woman. To others she was a kind of contemporary witch, able to manipulate people, particularly men, to her own ends and change identity at will.

Yet while some aspects of the drama were as old as the battle of the sexes, its plot was radically unconventional. Like some riotous postmodern novel, the McKinney saga boasted at least one unreliable narrator, a debate about the subjectivity of truth, a feminist subtext, a theme on artificial celebrity, and a kind of cruel authorial joke at the expense of all the characters, including the press itself.

Thirty-four years on, the tale has been retold by Errol Morris in a jaunty and yet perceptive documentary entitled Tabloid. The film looks at how myths are created both in the media and our own minds and suggests that even the most incredible falsehoods grow out of heartfelt desires. As Morris recently said about his film: "It's a ridiculous story. But people are wrong if they think the profound and the ridiculous are incompatible."

When a Mormon missionary by the name of Kirk Anderson went missing on 14 September 1977 near Epsom, news editors scarcely blinked. There was plenty else going on at the time. In this disappeared world, pop star Marc Bolan was to meet his end in a car crash on 16 September, unions were in discussions to save British Leyland, the Paedophile Information Exchange was organising public meetings, George Davis, the freed armed robber was rearrested for robbing a bank, and the tropical holiday arrangements of Princess Margaret and Roddy Llewellyn were held to be of national import.

But as the days, weeks and months unfolded, the back story to Anderson's abduction began to force its way into the headlines. By turns funny, kinky, sad and mystifying, it began in the Appalachian mountains, where McKinney, an only child, grew up in a small town in North Carolina. She was a bright and restless girl with a compulsive weakness for beauty pageants – which she frequently entered, seldom with success – and a strongly religious appreciation of morality. As she came of age her two guiding principles in life seemed to be celebrity and chastity. Perhaps inevitably they were destined to clash.

In 1973, having converted to Mormonism, she moved to Provo in Utah to study at the church's Brigham Young university. While in Utah she set about infiltrating the social circle around the Osmonds, the squeaky-clean family pop group that were the pride of the Mormon church. By various accounts she fashioned a relationship of sorts with one of the brothers, Wayne Osmond. In Anthony Delano's invaluable little book Joyce McKinney and the Case of the Manacled Mormon, the author notes that Olive Osmond, the family's matriarch, was sufficiently concerned to take steps to keep McKinney away from her boys. There were also reports that when Wayne later announced his engagement to another woman, McKinney was devastated.

Not long after the Osmond crisis, McKinney met Kirk Anderson and the couple starting dating. In Tabloid, McKinney, now a rotund 60-year-old, describes Anderson as though he were a heroic combination of Clark Kent and Gary Cooper. In reality he was an unprepossessing figure, overweight, ill-at-ease and, at 19, six years younger than McKinney.

According to McKinney, they slept together, she lost her virginity and, overwhelmed by guilt, Anderson confessed his sinful behaviour to Mormon elders, who promptly put a stop to the affair. Anderson was moved out of Utah, and then dispatched abroad to England on missionary work in East Grinstead, Reading and finally Epsom. McKinney claimed the tryst had left her pregnant and that she miscarried.

Appalled by the church's reaction, she turned her back on Mormonism, but not on Anderson. She pursued him across America, first to California and then to Oregon, where, in an effort to escape her attention, he lived under an assumed name. And when Anderson was then sent to England, McKinney employed a detective agency to find him.

With an accomplice, a man named Keith May, she embarked on her own mission: to get Anderson back. The two conspirators flew to England and, using an imitation handgun, abducted Anderson and drove him to a secluded cottage in Devon. Exactly what took place in the cottage during the following three days remains the subject of dispute. But all parties agree that at one stage the Mormon was tied to a bed while McKinney repeatedly had sex with him in an effort to become impregnated. McKinney has always maintained that the bondage was a game designed to ease Anderson's guilt about sexual enjoyment. Anderson insisted that he was effectively raped. After three days he was allowed to leave. McKinney and May were then quickly arrested and held on remand in prison for three months.

Although many British industries were in decline in the 1970s, the newspaper business was thriving, particularly at the tabloid end of the market. The biggest selling daily paper was the Daily Mirror, with a circulation of around 4 million. Close behind and rapidly gaining ground was the Sun, with its page three "stunners" and salacious populism. The Mirror liked to think of itself as a campaigning newspaper with a roster of celebrated columnists, but it was always on the hunt for titillating stories and few were more titillating than that told at Epsom magistrates court in late 1977.

McKinney had been desperately trying to get word to the press during her incarceration. When committal proceedings were held to decide whether the case should go to trial, she got her chance to go public. She demanded that reporting restrictions be lifted and then spoke at length to the court about such matters as the erotic benefits of oral sex, as reporters feverishly scribbled, unable to believe the gift of ready-to-print copy forming in their notebooks.

If McKinney was never quite the fabulous beauty of her imagination, she was blonde, shapely, with a sweet face and, most beguiling of all, a comely Southern accent. And she had read The Joy of Sex. As far as the press was concerned, she was the Scarlett O'Hara of sexual liberation.

The prosecution argued that McKinney was a stalker whose "all-consuming passion" had led her to abduct Anderson and force him to have sex. The barrister for the crown read out Anderson's submission: "She grabbed my pyjamas from just around my neck and tore them from my body. The chains were tight and I could not move. She proceeded to have intercourse. I did not want it to happen. I was very upset."

Alas the Daily Mirror was initially unable to publish this emotive testimony because it was unable to publish a newspaper, at least in the south of Britain. It was locked into one of its periodic industrial disputes, this time with the National Union of Journalists, and printing was suspended at its London presses. Fortunately the hearing lasted several weeks, enough time for the reporters to resolve their action and record McKinney's extraordinary final speech.

At one point in that bravura performance she held forth to the magistrates on the psychology of sexual submission. "I think I should explain sexual bondage and Kirk's sexual hang-ups," she said. "Kirk was raised by a very dominant mother. He has a lot of guilt about sex because his mother has overprotected him all his life… He has to be tied up to have an orgasm."

But the quote that was a sub-editor's fantasy came during the extended declaration of her feelings for Anderson. "I loved Kirk so much," she told the court, "that I would have skied down Mount Everest in the nude with a carnation up my nose."

As Jean Rook, the doyenne of the Daily Express, put it with characteristic understatement: "Never had a woman laid her soul and everything else so bare, or declared her passion in such richly scented, spine-chilling language."

It was as if McKinney had studied the tabloids and served them exactly what they wanted. Given that she had little else to occupy her for almost three months in Holloway prison, that is probably precisely what did happen. "She knew how to turn a phrase, did Joyce," says Mike Molloy, the Daily Mirror's editor at the time. "Like everyone else, and not just in the tabloid press, I was riveted."

But if she had the reporters eating out of her hand, the magistrates were less impressed. They referred the case to trial, although they did now grant her bail. And that's when the fun really started. Although she was obliged by her bail conditions to live with her parents, who had come over to Britain, and their temporary landlady in north London, McKinney soon set about enjoying her new-found fame.

With Keith in tow, she toured Fleet Street's offices looking to sell her story for £50,000. She promised to expose the Mormon church and the Osmond family, and took out an advertisement in Variety seeking the attention of agents and film studios. Her sharp routine in and out of court didn't go unnoticed. If she was capable of such show-stealing turns, news editors began to wonder, could her story of a sheltered life really make sense? And what had she been up to in the two years between leaving Utah and coming to England?

At the Mirror, Molloy had more urgent concerns. He was trying to build his spring advertising campaign around the sexual revelations of George Best, who was then living in Los Angeles. The series was to be called "The Best XI". Molloy despatched Kent Gavin, a photographer who knew Best, to California to persuade the footballer to confide his bedroom secrets.

Best wasn't interested but while he was in LA, Gavin received a tip-off that McKinney had once shared a flat in the city with a man named Steve Moskowitz. Gavin, a tenacious newshound, tracked down Moskowitz and promised to fly him to London to see McKinney's trial at the Old Bailey that was due to start in May.

"I had no idea what we were going to unearth," Gavin remembers. "He was an ex-boyfriend and he was crazy about her. It turned out that he was a real freak but he opened the doors for us."

The following day Moskowitz turned up at Gavin's hotel with a stash of photographs featuring McKinney in various nude poses, mostly with an S&M theme. He also told Gavin that the former Mormon had worked as an escort and that reporters from the Sun had been in touch with him, though he had told them nothing.

Fearing that the Mirror's rivals would beat him to the story, Gavin trawled through McKinney's phone bill, searching for soft-porn photographers and the all-important negatives. He also dug out adverts for McKinney's services in the classified sections of free magazines. "Spending that amount of money these days on what could have been a wild goose chase – it just wouldn't happen," says Gavin. "Those were the glory days of Fleet Street. Money was no object anywhere round the world." The whole investigation took him around three weeks but he found what he was looking for and headed back to London with a bulging file of lurid evidence.

The only problem was that the Mirror couldn't run the story. There were no moral doubts. Molloy and Gavin both thought that McKinney deserved to have her secret past exposed. As far as they were concerned, she was trying to make money out of a false image, conning not just the law but, perhaps less acceptably, the press. Yet anything published about McKinney before the trial would be contempt of court, and in April 1978 the trial suddenly looked like being indefinitely postponed.

Peter Tory is a former RSC actor who drifted, almost by accident, into journalism. When McKinney was doing the London rounds, Tory was deputy on the William Hickey gossip column in the Daily Express. He would go on to edit the column, but at the time his good friend, Peter McKay, who is now responsible for the Ephraim Hardcastle column in the Daily Mail, was in charge. Noting McKinney's popular appeal, McKay suggested that Tory should take the out-on-bail American along to the premiere of a Joan Collins film entitled The Stud.

Tory is the star of Tabloid. With his suavely diffident manner that is reminiscent of Bill Nighy, he's a gifted and entertaining anecdotalist. He tells me that his memory of the McKinney story has been kept active by repeated retellings at dinner parties over the past three decades.

"Peter [McKay] was always one for getting other people to do things," he recalls. "So I dressed up in a dinner jacket and put dark glasses on and turned up outside the Empire with Joyce McKinney in a Rolls-Royce. There were a great number of photographers. She enjoyed every minute of it, behaving like a seasoned Hollywood star, posing this way and that way for the cameras. Any idea that she'd been exploited by anybody is absolute nonsense."

Photographs of the event show a beaming McKinney in the kind of dress Elizabeth Hurley would later make a career falling out of. Whatever McKinney was projecting, it wasn't an image of God-fearing modesty. Tory recognised a fellow performer, someone who slipped so effortlessly into a role that she became the act and the act became her.

"When I went to Ascot with a top hat, I was rather like Joyce McKinney," he says. "I used to believe I was William Hickey. The strange thing about being William Hickey is that there were people who thought you were William Hickey. I remember Jeffrey Archer once calling me up from New York trying to impress some publisher. He said, 'Is that Bill?' I said, 'Who's this?' He said, 'Jeffrey Archer.' I said, 'It's Peter Tory here Jeffrey, why are you calling me Bill?' 'Ah Bill, how are things? How about lunch next Wednesday, Bill?' So one played this sort of strange double role."

For Tory the McKinney stunt was just another mad adventure in what was a non-stop Fleet Street party, before newspapers were dispersed to hermetically sealed offices in different corners of London. He reminisces about the expenses-fuelled largesse that brought together journalists from rival papers in drunken unity. "Mike Molloy used to phone me up at 12.30 and say 'Peter do you fancy a drink?' And I'd go into his office and have a drink and there would be two Jaguars in the underground car park of the Mirror building that had been warmed up with chauffeurs ready and all of us hacks would be driven off to El Vino, which was only about 300 yards away, and then we would spend about two hours there drinking. And not fine wine but drinking large whiskies. To my certain knowledge, in those days most of the papers were written and edited by people who were technically drunk."

One of the most striking contrasts in this story is between the female teetotaller McKinney and the hard-drinking male hack pack. For a while at least, it was the sober American who outwitted the inebriated Britons. Within days of The Stud premiere, McKinney had vanished. She didn't turn up at the police station as required by her bail agreement. Instead, with the help of her landlady, whom she had charmed to her cause, she and May assumed the identities of two dead Mormons and slipped out of the country in disguise, pretending to be a pair of deaf mutes.

Initially Tory felt as though he'd been duped, used as a kind of decoy, as McKinney readied herself to flee. Then one evening, a week or so later, in his office, he received a call from McKinney, who was back in the States.

"She said she wanted to sell her story to the Daily Express," Tory recalls. "She gave me all this bullshit that it was the only paper she trusted and I was the only journalist she trusted. She said she wanted £40,000 in a suitcase. I said, 'Just hold on', and I went through to Derek Jameson's office, who was the editor. I said: 'I've got Joyce McKinney on the telephone and she wants to sell her story to us.'

"Derek nearly fell off his chair. 'Fuck me,' he said, 'what does she want?' I said she wants £40,000 in a suitcase, and so he said, 'Well give it to her, give it to her.' So I rushed back to the phone and told her that would be fine, and where was I to meet her."

Armed with a worrying amount of cash, Tory flew out to meet McKinney and May at the Hilton Atlanta Airport. The two fugitives turned up in greasepaint, dressed "like characters from a really bad amateur production of Ali Baba", recalls Tory. As a gossip columnist, he didn't have any experience of major stories so the Express sent along the head of their New York bureau, Brian Vine, and a photographer, to help out.

Paranoid about the FBI, whose agents she feared were tracking her, McKinney insisted that the group move from hotel to hotel around the southern states as Tory took down her story. It was a largely anodyne if self-glorifying narrative, and Tory believed every word. "She told it in a colourful way," recalls Tory, "but there was no sense that she had ever been anything but a sweet country girl and she got caught up in this business in London, and everything was part of a Mormon conspiracy. I thought it was a bit boring really, but I thought, here am I involved in a great scoop. I was never a proper reporter."

Meanwhile, in London, the Mirror had got wind of the Express's "scoop". In one sense the Mirror team was disappointed. They hoped that it would be the Sun that swallowed McKinney's apple-pie ramblings. But it also meant that the Express was going to risk contempt of court charges, which strengthened the Mirror's own case for publishing. In any event the word Molloy was hearing was that neither the British police nor judiciary were keen to see McKinney back in the country or the dock. To all intents and purposes, the trial was history.

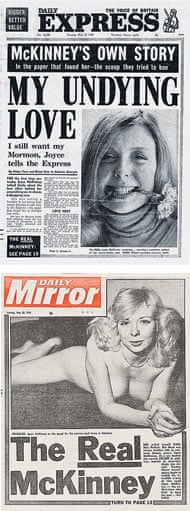

So it was that on Monday 22 May 1978, the Daily Express published the Joyce McKinney story under the front page headline "My Undying Love". She was photographed in a roll-neck sweater, smiling with a carnation in her teeth. "For the first time yesterday," read the opening paragraph, "Joyce McKinney talked freely about the love affair behind her astonishing sex-in-chains kidnapping case." She described her love for Anderson as "tender, profound, indestructible".

On the same day, the Daily Mirror also had McKinney on its front page. This time she was naked and staring at the camera with a less-than-innocent expression. The headline was "The Real McKinney" and the report began: "She called herself Little Miss Perfect. But there was another side to the runaway beauty queen Joyce McKinney. As a sex hostess she earned $25,000 in 18 months on America's shady vice circuit."

Seldom can two newspapers have run such graphically contrasting versions of the same story on the same day. Holed up in a hotel in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, McKinney, Tory and the rest of the extended group waited to hear news of how the Express story had fared in Britain, all of them utterly unaware of the Mirror's contribution. When a friend of McKinney's phoned and told her what had happened, she became hysterical.

"It was like something from The Exorcist," says Tory. "She screamed and screamed and she appeared to me to be about to jump off the balcony. She ran for the balcony and tore the curtain down. I thought, God, she's going to go over the edge and there were these American tourists underneath in deck chairs – she would have taken them with her."

Tory and Vine took McKinney to a nearby hospital, where she was sedated. They then called her parents who arrived at the hotel early the next morning. By then the effects of the sedative had worn off and McKinney became upset again, going so far as to sink her teeth into her father's arm. The commotion drew attention, as Tory recalls: "Two state troopers turned up in cowboy hats and dark glasses in this small hotel room that had all these people in there: me, Brian, the photographer, Keith May, the parents and Joyce. Joyce was sitting there looking like Ophelia in a nightie, staring eyes and her hair all over the place, and Keith May looked very alarmed. The state troopers asked us what was going on, so we tried to explain the story to them. One of them – it was like Laurel and Hardy – he actually took his hat off and scratched his head at one stage as we were talking about East Grinstead, Mormon church, tied to the bed. They were completely baffled by it."

They weren't the only ones. The following day the Express tried to dismiss claims of a "lurid past". "At no time," Keith May was quoted as saying, "did she pose in the nude." The same day the Mirror ran photographs of her sitting on a horse, entirely unencumbered by clothing. The Express gave up. Jameson, the editor, walked into the pub next door to the Mirror, announced his "surrender" and bought everyone a drink, and his paper made no further mention of McKinney. But the Mirror ran still further revelations, illustrated with images of McKinney in various states of undress with whips and other suggestive props. Only the announcement on the Friday of a crisis in the Lib-Lab pact finally forced McKinney off the front page.

Six years later McKinney was arrested at Salt Lake City airport, where Anderson worked. In her car were a set of handcuffs, some rope and a notebook detailing Anderson's movements.

To this day, McKinney, who has never married, maintains that hers was "the greatest love story ever told", and dismisses the Mirror exposé of her LA years as malicious fabrication. In Tabloid, Morris sensibly avoids taking sides, allowing the various protagonists to put forward their own recollections without editorial comment. The result has not pleased McKinney, who turned up at several screenings around the States protesting against a film in which she had been a willing participant.

By contrast, Tory and Gavin both sing Morris's praises. What they are less positive about is the current state of tabloid papers. Molloy agrees. "Newspapers were smaller and handmade and it was all done with a lot more nervous energy," he says. "We really did believe we were a power for good. The pops now are not a vestige of what they were in my day. They simply report celebrity culture. Fleet Street became coarser and more competitive, and it ended with phone hacking."

But in a sense the McKinney story was a prototype of today's celebrity culture, in which dreams dwarf talent and attention trumps application. Her misfortune was to live in an era before X Factor and Big Brother. Had she been a young woman today, she might have lived out her starry ambitions in her 15 minutes of fame. As it was she put her creative energy into a romance with a man who didn't want to be tied down, at least not in the way that McKinney wanted. Thus she was immortalised by the tabloids. In the end, her story was as ridiculous and as profound as that.

Errol Morris's film Tabloid is on general release from 11 November

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2011/oct/16/mckinney-mormon-missionary-sex-tabloid

0 Response to "According to Joyce Sexual Force Feeding Leads to"

Post a Comment